Tiny New Lasers Fill a Long-Standing Gap in Visible-Light Colors, Opening New Applications

September 3, 2024

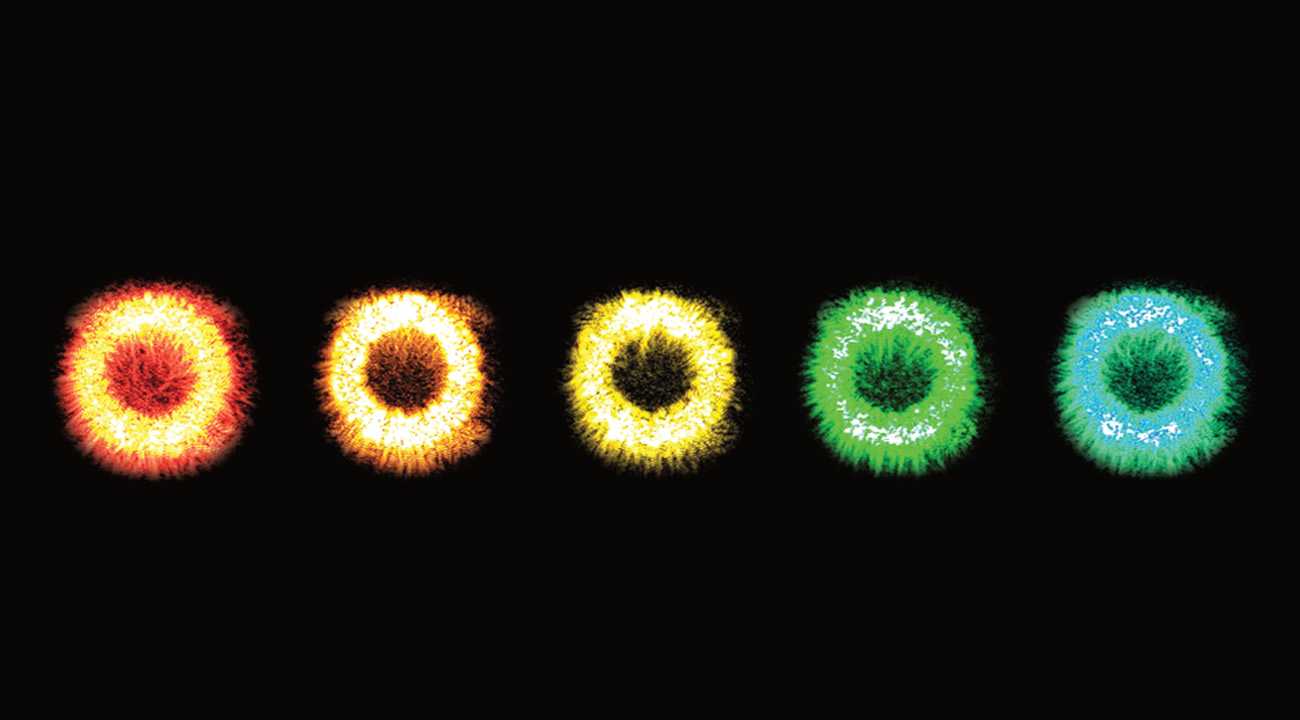

Series of visible-light colors generated by a microring resonator. (Credit: S. Kelley/NIST)

It’s not easy making green.

For years, scientists have fabricated small, high-quality lasers that generate red and blue light. However, the method they typically employ—injecting electric current into semiconductors—hasn’t worked as well in building tiny lasers that emit light at yellow and green wavelengths. Researchers refer to the dearth of stable, miniature lasers in this region of the visible-light spectrum as the “green gap.” Filling this gap opens new opportunities in underwater communications, medical treatments and more.

Green laser pointers have existed for 25 years, but they produce light only in a narrow spectrum of green and are not integrated in chips where they could work together with other devices to perform useful tasks.

Now a team led by JQI Fellow Kartik Srinivasan, who is also a Fellow of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, has closed the green gap by modifying a tiny optical component: a ring-shaped microresonator, small enough to fit on a chip. They describe the new technology in an article published August 21, 2024 in the journal Light: Science & Applications.

A miniature source of green laser light could improve underwater communication because water is nearly transparent to blue-green wavelengths in most aquatic environments. Other potential applications are in full-color laser projection displays and laser treatment of medical conditions, including diabetic retinopathy, a proliferation of blood vessels in the eye.

Compact lasers in this wavelength range are also important for applications in quantum computing and communication, as they could potentially store data in qubits, the fundamental unit of quantum information. Currently, these quantum applications depend on lasers that are larger in size, weight and power, limiting their ability to be deployed outside the laboratory.

For several years, Srinivasan and his team have used microresonators composed of silicon nitride to convert infrared laser light into other colors. When infrared light is pumped into the ring-shaped resonator, the light circles thousands of times until it reaches intensities high enough to interact strongly with the silicon nitride. That interaction, known as an optical parametric oscillation (OPO), produces two new wavelengths of light, called the idler and the signal.

In previous studies, the researchers generated a few individual colors of visible laser light. Depending on the dimensions of the microresonator, which determine the colors of light that are generated, scientists produced red, orange and yellow wavelengths, as well as a wavelength of 560 nanometers, right at the hairy edge between yellow and green light. However, the team could not generate the full complement of yellow and green colors necessary to fill the green gap.

“We didn’t want to be good at hitting just a couple of wavelengths,” says JQI Postdoctoral Researcher Yi Sun, an author on the paper. “We wanted to access the entire range of wavelengths in the gap.”

To fill the gap, the team modified the microresonator in two ways. First, the scientists slightly thickened it. By changing its dimensions, the researchers more easily generated light that penetrated deeper into the green gap, to wavelengths as short as 532 nanometers (billionths of a meter). With this extended range, the researchers covered the entire gap.

In addition, the team exposed the microresonator to more air by etching away some of the silicon dioxide layer below it. This had the effect of making the output colors less sensitive to the microring dimensions and the infrared pump wavelength. The lower sensitivity gave the researchers more control in generating slightly different green, yellow, orange and red wavelengths from their device.

As a result, the researchers found they could create more than 150 distinct wavelengths across the green gap and fine-tune them.

“Previously, we could make big changes—red to orange to yellow to green—in the laser colors we could generate with OPO, but it was hard to make small adjustments within each of those color bands,” Srinivasan says.

The scientists are now working to boost the energy efficiency with which they produce the green-gap laser colors. Currently, the output power is only a few percent of that of the input laser. Better coupling between the input laser and the waveguide that channels the light into the microresonator, along with better methods of extracting the generated light, could significantly improve the efficiency.

This story was originally published by the NIST News. It has been adapted with minor changes here. JQI is a research partnership between UMD and NIST.

In addition to Srinivasan and Sun, JQI Postdoctoral Researcher Jordan Stone, JQI Assistant Research Scientist Xiyuan Lu and Zhimin Shi from Meta’s Reality Labs were also authors.

Experts

People

![a photo of a man wearing a blue and white checked shirt in front of greenery]()

Kartik Srinivasan

Adjunct Professor, JQI Co-Director

![Picture of Yi Sun]()

Yi Sun

Assistant Research Scientist

Groups

JQI